The Innovative Training Network WEGO (“Well-being, Ecology, Gender and Community) was born in the Convent of Santa Maria del Giglio in Bolsena, Italy, resulting from the meeting of several women active in academic research and feminist organisations. The Institute of Social Studies of the Erasmus University in The Hague was responsible for organising the meeting in July 2016, which allowed to share research done and various practices motivated by a deep concern around the ecological crisis and global inequality. The exchange was oriented towards the preparation of an academic project aimed at supporting doctoral students from different parts of the world to investigate around topics associated with Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) and the care economy, transcending the logic of individual theses to work in a collective process that would reflect in practice the vision of transformation that guides the project. In January 2017 this one was presented to the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska – Curie research and innovation programme, which granted its support to the initiative. In 2018 it began to operate with 15 doctoral students, scholar-activists working in ten universities in Germany, Italy, Norway, Spain, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom where the students are doing their PhDs, and ten partner institutions in Australia, India, Indonesia, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, Uruguay and USA, which accompany the students in their field work with a role of training and secondments.

In those exchanges that resulted in the creation of the network, there was not only a deep concern about the global crisis in its multiple dimensions, but also about the big picture response anchored in the very same processes and views that originated the current situation. That is, mainstream development policies and programs, even if under the name of Sustainable Development Goals, Green Economy and other denominations, aim at continuing with business as usual under a name that seems to be more caring for the environment but that only deepens the dominant practices and their negative impacts on life in its diversity. In response to this situation, a group of scholars and socially engaged women came together around two core ideas: the potential of transformation and innovation of Feminist Political Ecology and the need for another type of research that is based on epistemic justice and makes visible the knowledge and everyday strategies pioneered by ordinary people and communities. From there, the following objectives were agreed upon:

- Establish a network of excellence around FPE that links researchers, communities and policy makers so as to have an impact in the environment and development policy arena and contribute to positive change for the communities involved in the research.

- Support the emergence of a new generation of Early Stage Researchers in a societally relevant research platform.

- Consolidate FPE as a key conceptual approach to resilience and sustainability by bringing fresh perspectives on gender to the policy space of environment and development opened by the SDG.

Feminist Political Ecology is at the centre of the work carried out by the network. As with other concepts, we could not present a single definition, nor does WEGO have a final agreement on what all of its members understand about this shared framework of analysis. The collective construction of the conceptualization about FPE is part of the challenge. Several ideas are part of this conceptualization and motivate the work of the network:

- FPE looks at the dynamics of gender relations and how they determine ecological, technological, political and economic processes. It analyses how gender power relations shape resource access and control; the decision-making processes and socio-political forces that influence development and environmental policies; the way in which policy can take into account the complex layers that make up people’s relations to their environment; the culture- and knowledge- specific influences into sustainable practices; knowledge production related to nature (and processes by which some of these are made irrelevant by the dominant perspective); the relations between humans and non-humans; among other dimensions.

- Feminist political ecology questions the simplification of adding women to statistical data and the narratives that present women as victims of environmental crisis. It highlights the engagement of women as political actors with the capacity to produce relevant knowledge, implement creative and sustainable ways to relate to nature, question power relations that reproduce gender inequalities in decisions about environmental policies. It looks at day to day experiences with a politically aware approach that promotes grounded and engaged research to understand and made visible political processes including the emotions and embodied reactions and responses of people and communities to economic, social and environmental change, in order to promote sustainable alternatives, resilience and wellbeing.

- The structuring axis of FPE is relational, based on the recognition of the interconnectedness of all forms of life. While the dominant patriarchal mode of development is based on domination and exploitation (over bodies, cultures, nature), FPE promotes a transition based on the day to day practices of women, men, transgender, queer, non-binary and other subjectivities and their communities to sustain ecologically viable livelihoods. The shaping of these livelihoods takes place within the tension between autonomous and diverse imaginaries and the impositions of capitalist globalisation.

In order to contribute towards this transition, WEGO set out to research around three main themes:

- Climate Change, Economic Development and Extractivism

Under this theme, the research centres on community responses to climate change, neoliberal capitalism and extractivist development processes. The focus is on the daily social struggles in response to economic and ecological changes, and on the organisation of communities and their efforts to overcome situations of inequality, exclusion and poverty. Among the areas to be addressed are “the cultural dimensions of gender and the politics of transformation” that allow us to show how the new socio-material arrangements are shaped by and in turn shape new cultural repertoires, offering or imposing new cultural ways of being, relating and identifying.

Although in each topic there is a diversity of subtopics that students investigate, the shared framework in this case includes the following concerns: connections that are shaped by new modalities and scales of governing the resources from regulation by national governments towards investment agreements, and from regional and national to international scales; forms of social mobilisation to defend water and food security, energy, livelihoods and demand fair labour conditions in new ways of articulating scales of governance and connecting people; nodes of connection and alliances across different spatial scales, looking not only at the material and socio-spatial elements of resource-reallocation and commodity production but also at histories of class- caste- and gender struggles.

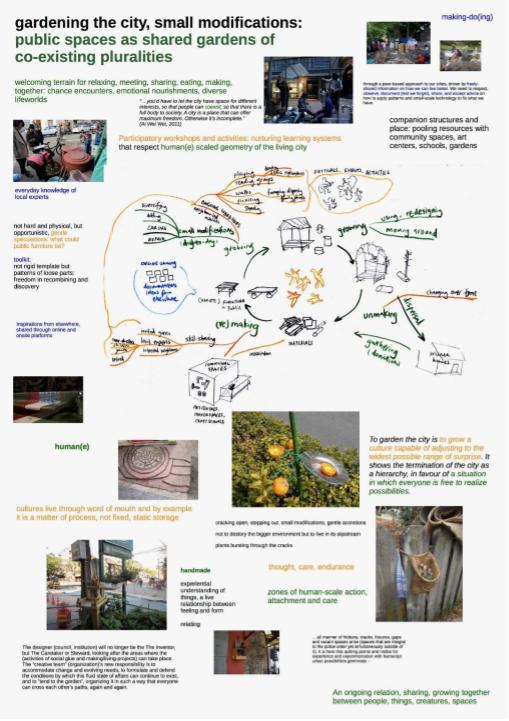

2. Commoning, Community economies and the politics of care

In this topic, the exploration focuses on identifying how different communities are producing new forms of resource management based on non-extractivist development practices as well as survival strategies based on community economic practices and the value of care and living well together. The focus of the various research projects will be on the emerging practices of communing, community economies and care from a gender perspective.

The shared frame for this theme has to do with observing how communities are being more resilient and sustainable, for which some common observation points are: ‘commoning’ efforts to both promote the recovery of food security and their communities; care practices in interconnected spaces; subjectivities (masculinities and feminities) to create and enable a more inclusive community and commitment to place; market rationalities in the shift to alternative ideas of sustainable livelihoods; entrepreneurial practices and resource management by community groups linking rural producers and urban consumers; political and ecological consequences of new value chains and how they intersect with notions of class, gender, religion (caste) and age.

3. Nature/Culture, technologies and embodiment

This topic engages with the interdependence of bodies, ecologies and technologies in the studies of body politics and political ecology. The focus of this theme is on communities embodied experience of economic and ecological change and ways to think beyond assumed technological, scientific and social boundaries between nature and culture.

Within the framework of this topic, the research transcends the conventional approach on nature that separates human beings from their environments, and aims to analyse how bodies, technologies and economies should be understood as an integral part of our material environment and of ecological practices and theory. Common aspects to be analyzed include: the concept of nature-culture and how to look at the interrelationship between humans and non-humans in the framework of changing ecologies and economies; the emerging narratives that can unmake and make new worlds as we reinvent and “turn” to new eco-criticism and new eco-politics; the interdependence of technologies, ecologies and bodies and their implication in political frameworks for sustainable development.

WEGO in 2021 and beyond

The 15 research projects were proposed within the framework of these three major themes and in 2019 several of them began their field work. The global pandemic of COVID 19 had an impact on these projects and on the network as a whole, as it has happened massively throughout the world. WEGO’s work continued in 2020, primarily in virtual form. Some projects were reformulated, in some cases in dialogue with the communities and groups based in the different territories, in others remotely given the emergency that determined the return of several of the doctoral students to their places of study or prevented the development of field work. In spite of these difficulties, a Training Lab was organised in June 2020 for all WEGO members, where each of these projects was analysed and debated in depth, and thorough debates also took place around the very conceptualisation of feminist political ecology.

Before and after the Training Lab, the students have been working among themselves and with the rest of the network around changes and tensions in relation to the projects: categorisations, concepts, emergence of questions linked to epistemic violence, privileges within the academy, situated knowledge and the role of Eurocentric institutions, research ethics and its relationship with a care perspective, among several other dimensions. The path travelled, the learnings and new questions, the exchanges inside and outside the network, generated interest in capturing this process and the exploration around Feminist Political Ecology in a publication. The idea is to work collectively towards the completion of the projects and, through this publication, contribute to generate a dialogue around FPE and its possible contributions towards a social, economic and ecological transition (transitions). Likewise, and as part of that process of contributing to the conceptualization of FPE and of strengthening networking and diversity, members of WEGO will contribute with articles and other inputs to be shared in this same space.