The Lalang river, in Indonesia, is a common property for the Murung people – almost all Murung activities happens on or around the river. However, catching fish has become more difficult for the Murung women when extractive projects such as coal mines operate in the region. Photo credit: Siti Maimunah.

In July this year, four of us (Nanako, Mai, Martina and Enid) came together online to present our work and bring a feminist political ecology perspective to debates and discussions happening at the IASC-RIHN Online Workshop On Commons, Post-Development and Degrowth in Asia. This is what we presented – and learned.

With issues of commons and commoning, the more-than-human and care, all featuring in our PhD work, we were keen to learn about the diverse meanings of the commons, their intersecting power dynamics and transformative potential in the context of Asia. For instance, what similarities and differences are shared among commons studies in Asia? Do they go beyond hegemonic formulations introduced by Western concepts, which are often carefully attended to by Asian scholars and in Asian studies? Indeed, using exogenous terms and concepts entails challenges in terms of linguistic and epistemological incompatibility. So why is it necessary to translate locally embedded terms? Nanako touched upon this challenge through questioning the necessity of linguistic and semantic translations in relation to aging, a universal concern, and the specificity of Japanese rural communities and the associated traditional landscape or Satoyama.

Mai brought the topic of extractivism to the workshop, through the example from her fieldwork where indigenous communities who depend on rivers in Central Kalimantan to sustain their livelihood have experienced the spatial reorganisation of communal forests and agricultural lands, which are being converted into coal mining areas to pursue economic growth. She was interested in questions such as, how do experiences of extractivism relate to commoning practices? Do principles of degrowth support the struggles of people affected by extractivist projects?

This workshop therefore offered us an opportunity to learn and think with others about different commoning practices happening in Asia, and also tackle difficult, often uncomfortable questions about how they are being represented and narrated in degrowth and post-development scholarship. These tensions and our interest in confronting them were further articulated through Enid’s presentation of the idea that a just Degrowth is a Decolonial Feminist Degrowth. The plurality of thinking and praxis around Degrowth, the commons and post development, we found, like feminisms, are infused with constructive tensions and contestation.

We were particularly inspired by the way that the studies presented at the workshop embraced and enriched the practice of working, thinking and researching with situated knowledges. Among the many inspiring presentations, discussions and debates happening both on zoom and the online conference platform, Slack, there were, two presentations that resonated with us: “Gradual Stiffening through Making-Do: A Method of Hope for Degrowthing Shared Public Spaces” by Chris Berthelsen, Xin Cheng, Rumen Rachev and “Covid-19, Common, and Life within Society: Indonesian Case” by Nur Dhani Hendranastiti.

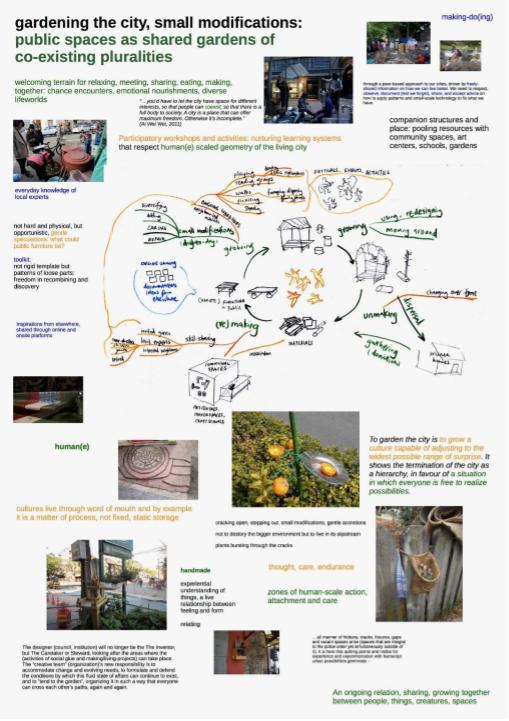

The former presentation was on the possibilities of collective hope in urban commons and commoning practices. Beyond visions of urban commons as fixed urban spaces, they suggest a re-orientation of notions of property and shared urban spaces and places, that are lived through a method of collective hope, thinking and operating beyond the human, and which is made and remade through the opening up of possibilities which can only exist in ambiguity and uncertainty. Related to this, earlier work by Xin Cheng and Chris Berthelsen explored how small co-habitations might work on a larger community scale through the below ‘hallucination.’ Their collaborations in themselves are inspiring to think through the multiple practices of knowledge co-production in relation to shared spaces and commoning practices – especially in their attentiveness to their more-than-human fellows! You can see more work by Xin Cheng on reframing urban socialities in Hamburg here and read her book on co-producing ‘human(e) shared spaces’ here.

The second presentation by Nur Dhani Hendranastiti, explored the correlations between Islamic ethical principles and degrowth principles. Ethical principles such as Amanah (trust), Adalah (social justice) and Ihsan (equilibrium through distribution) were at the core of the agricultural-financial system that supported farmers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Decentering capital, the system privileges multiple stakeholder equality, including non-humans. Ecological economics and degrowth thinking often refers to ethical principles from Buddhism, (often drawing on the work of Schumacher) but rarely other religions. Whilst the financial system described still worked within the confines of a capitalist system and norms of individual property ownership, Nur Dhani Hendranastiti challenged us to think beyond what may have become dominant narratives about the ethical principles that guide degrowth.

Through the full but enjoyable three days of presentations, discussions and online chats, we were able to connect to a variety of different scholars and artists who helped us to develop a deeper understanding of the debates and practices on commoning, degrowth and post-development in Asia. In that learning and interacting process, we were commoning our knowledge, re-imagining a world full of plurality. Through our own collaborative presentation, we introduced the different issues, concerns, activisms, communities and theoretical frames we are working with and offered a brief intervention from a feminist political ecology perspective on some of the key theory and ideas coming from degrowth, post-development and commons scholarship. The diversity of perspectives made visible at this workshop demonstrated the dynamism of these intersecting disciplines and practices, and created a hopeful and careful space to remain curious in these challenging times.