Notes from “Women in Graassroots environmental justice movements”, CSW66 parallel event, organized by Pangea Foundation and WEGO-ITN, March 22nd, 2022.

Women from marginalized territories are often overlooked when speaking of women’s leadership, but they are often at the frontline of environmental justice movements. To share their powerful stories, Pangea Foundation and the EU funded Innovative Training Network WEGO – Well-being Ecology Gender and cOmmunity on feminist political ecology have organised an online parallel event in the context of the 66th Session of the United Nation Commission on the Status of Women.

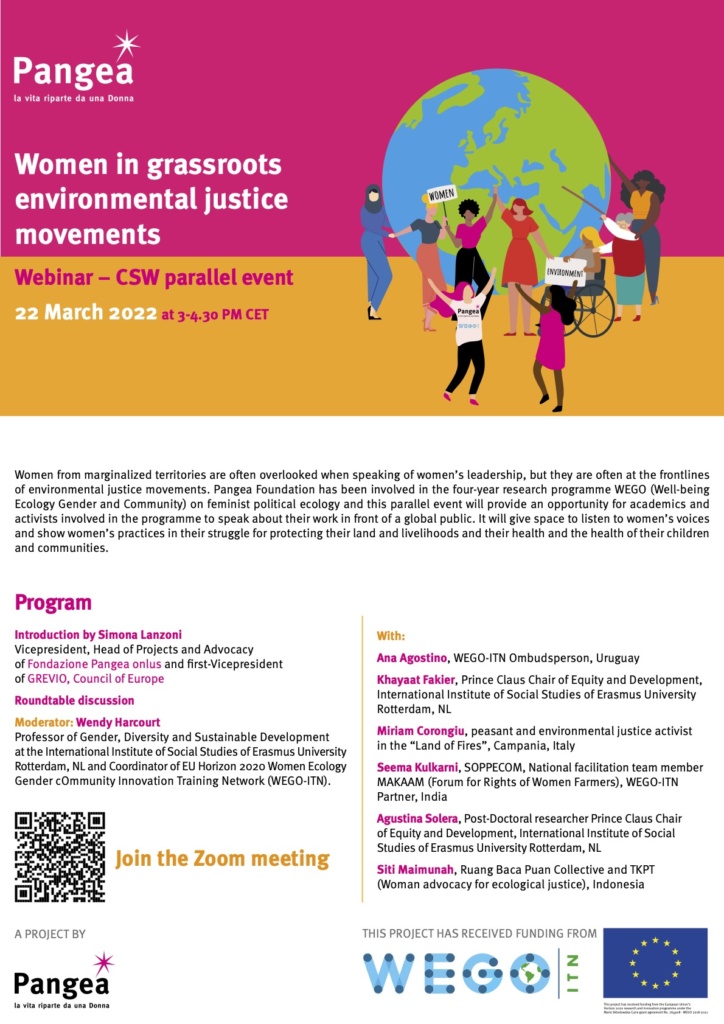

The webinar was introduced by Simona Lanzoni, Pangea Foundation’s vice-president, followed by a roundtable discussion moderated by Wendy Harcourt, Professor of Gender, Diversity and Sustainable Development at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), The Hague, Netherlands, both members of the WEGO network. Speakers were from different backgrounds: researchers, activists, and farmers and they shared their story of activism or research with women grassroots movements for environmental and social justice. Ana Agostino, WEGO’s ombudsperson, from Uruguay, who has been ombudsperson of the city of Montevideo for five years, shared a story about Vecinas (female neighbours), a grassroot group of women of the city of Montevideo, concerned about what was happening not only to them personally, but to the community at large. Khayaat Fakier, Prince Claus Chair on Equity and Development 2021-3 at ISS, from South Africa, spoke about the Rural Women Assembly, a self-organizing movement of women farmers, spread across thirteen countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Miriam Corongiu, a farmer from the so-called Land of Fires, Campania, Italy, shared her experience as a farmer and activist in an environmentally degraded territory within the networks Citizenship and Community, Stop Biocide and the ecofeminist group Georgica. Seema Kulkarni, from India, national facilitation team member of MAKAAM – Forum for Rights of Women Farmers, spoke about women coming from farmer suicide households. Agustina Solera, Post Doc Prince Claus Chair on Equity and Development at ISS, from Argentina, shared her experience with the Mapuche Community in Patagonia, Argentina. Siti Maimuna, WEGO PhD student at the University of Passau, from Indonesia, told her experience with the local anti-mining movement, the women’s organization TKPT, working with women in communities affected by mining, the indigenous people’s organization OAT, led by indigenous women in the island of Mollo and other NGOs in Kalimantan Island, campaigning for water justice.

Siti Maimuna’s story is a story of resistance, a story of women resisting extractivism. When mining companies arrived in Indonesia, women opposed the destruction of nature by occupying the territory with their own bodies. According to Siti Maimuna the human body is part of nature, therefore “opposing the destruction of nature is the same as refusing the destruction of the human body” and “the human body and the body of nature cannot be separated”. In Indonesian, “we call the human body Tubuh, and the nature or the territory where the body belongs is Tanah Air, Tanah means soil, and Air implies water. We call[ed] this the resistance to defend Tubuh-Tanah Air. Defending the bodies”. Women led the resistance against mining, activists organized demonstrations and created songs that were sung in every forest as a form of protest and resistance. Some of them decided to bury their feet in cement in protest mining companies and this act became a symbol of resistance. Eventually some companies left the area and since then, every two or three years, women organize a festival to celebrate the resistance and its success.

Agustina Solera’s experience refers to the time of her PhD research, in the Andean area of Patagonia, Argentina, with the Mapuche community and their schools in rural areas. She wanted to learn from the Mapuche’s ‘way of being in relation’, a way of being sustained on care and respect for the weave of life and its regeneration. When Agustina Solera got the opportunity to meet the population she learnt the fear, the stigma and the shame associated with being Mapuche. She recounted that “schools in Argentina played a main role in “civilizing” the surviving indigenous populations, erasing, denying or, in the best case, devaluing ancestral ways of being in relation (between humans and other-than-humans)”. Now, instead, “rural schools have become places of belongings in which struggles for resistance and re-existence germinate; have become fertile spaces where people from different cultures encounter each other.” Here, we see that the struggle for the reconstitution of language, knowledge, history and culture silenced in the past are not separable from other struggles of environmental and social justice.

Seema Kulkarni’s experience with MAKAAM and women farmers from suicide affected households in the state of Maharashtra, India is a story of agrarian distress, caused by the commercialisation of agriculture. The lobbying from the pesticide and the chemical industries led to an increase in the cost of cultivation and to a transition from a decentralized model to a corporate model of food production. All these factors contributed to an increase in farmers’ suicides, in particular in those states that were rapidly industrialising, and agriculture was increasingly seen in the commercial space.

The women of farmer suicide households are never visible. The state and its programs have not recognised them as workers and farmers in their own right. “Makaam story starts from there, politicizing this issue, centralizing the question of women farmers as farmers and not just as widows of these farmers,” said Seema Kulkarni. These women were dispossed of their rights, the majority of them never had access to the land that belonged to their family, and they were suffering also the stigma associated with their husbands’ suicide.

The movement’s action that took place in the capital of the Maharashtra state got a lot of attention from policy makers. These women started to be seen as a political category that demanded attention and a different kind of policies. But there was more. Women were saying that during the Covid-19 pandemic the commercialisation of agriculture left them without food, and they wanted real change. They said no to chemical fertilizers and no to chemical pesticides because they didn’t want to be controlled by corporations, they wanted their knowledge and their understanding of their farms to be at the forefront.

Miriam Corongiu’s story is of resistance and care from the so-called Land of Fires, Italy, a land where two million people live, characterized by toxic fires of illegally discharged waste, big polluting mega infrastructures (such as incinerators and gas power plants), and a phenomenon called ecomafia, organized crime connected to corrupt politicians and irresponsible managers. “It’s right here that agroecology is more necessary” stated Miriam Corongiu, “especially agroecology made by women, because of its attention to the regeneration of the relationship between nature and human beings, not only to the organic techniques to cultivate the land.” She is a member of several grassroots movements in Terra dei Fuochi, such as Stop Biocide and Citizenship and Community network, and part of an ecofeminist group of women, Georgica, all of them cultivating gardens, trying to fight for food sovereignty and agroecology.

Khayaat Fakier shared the story of the Rural Women Assembly of South Africa, a country deeply affected by the consequences of climate change that make farming and the provision of healthy food and nutrition to children and communities extremely difficult. A group of women coming from a very arid land not far from Cape Town tried to engage with the local and national government in order to obtain access to land for the production of food, but they were quite unsuccessful. Then, thanks to the interaction with a group of fisherwomen through the Rural Women Assembly, they started aquaponics production of vegetables, a mode of production where plants are planted in water. The water is populated by fishes, which feed from the nutrients and the oxygen that the plants emit into the water and, at the same time, the fishes fertilize the water. Both groups of women benefited from the initiative. This is an example of how the idea and notion of agroecology isn’t separate from food production for the communities and “demonstrates a way in which women working in nature can build collaboration in order to not just improve their own conditions and the conditions of the community but to collectivize the struggle for access to production” said Khaayat Fakier.

Ana Agostino’s story takes place in Montevideo, Uruguay, where the Vecinas, a group of local women, gave the impetus to an urban regeneration project in the city center. Women from the neighborhood brought to the attention of the ombudsperson of the city of Montevideo the problem of abandoned houses in the city center. This led to the creation of a program called Fincas Abandonadas, a project with the purpose of recovering abandoned deteriorated houses located in the central area of the city and restoring their social function. The municipality organized consultations with the local citizens and found three uses for these abandoned houses. First, dispersed housing cooperatives: houses owned collectively that in spite of being all in the same plot, were dispersed within the neighborhood; second, a Trans House, in response to the LGBTIQA+ community’s need to have a collective space for people who had someone in the process of gender change in their families. Third, a Half-way home, a secure home for people facing difficult situations, such as domestic violence, homelessness, having come out of different types of institutionalizations, etc.

The story of the Vecinas of Montevideo and their complaints about abandoned houses “is a clear example of this continuum between the day-to-day life of women who inhabit their space with a sense of community, and how they help in the definition and implementation of policies that contribute towards a better life for their communities and for the environment,” said Ana Agostino. Moreover, this case demonstrates that care for the environment where women live in, is not limited to the rural space, but it also includes the urban.

In conclusion, the speakers highlighted what emerged from the discussion and the stories shared during the webinar. Miriam Corongiu stressed the importance of care: care for the land, the community, loved ones and family; Khayaat Fakier the need of enhancing transnational solidarity, making connections within and across movements, between the rural and the urban spaces; Siti Maimuna stated that we have to learn how to reconnect with each other and nature, underlining that “knowledge restitution is very important and we have to start thinking about how the resistance and the struggle is experienced in our bodies.” Seema Kulkarni pointed out that “all of these stories are powerful stories saying that women are organizing, women are collectivizing, and they are looking at alternative ways of living, creating this world”. Ana Agostino concluded by saying that these stories were stories of women’s resistance, but “the resistance we are talking about is a creative resistance reconstituting a way of being in relation with others and to nature”.