This series of events was organised by WEGO-ITN Early Stage Researchers Dian Ekowati, Siti Maimunah, Alice Owen and Eunice Wangari, plus Prof. Rebecca Elmhirst, as a mentor.

The British version of WEGO-ITN’s Feminist Political Ecology Dialogues happened between the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022 in two separate occasions: on the The United Nations COP26 Peoples Summit for Climate Justice and as part of the Despite Extractivism Exhibition, organized by the Extracting Us Collective.

1. WEGO-ITN at UN Climate Change Conference

The United Nations COP26 took place in Glasgow, UK in November 2021 and was the focus for our first FPE dialogue event series.

We invited the public, through the COP26 Peoples Summit for Climate Justice events programme, to join us to discover stories from Indonesia, Kenya and the UK which can be woven together to tell a bigger story about the making of climate colonialism, the logics of extractivism, and the ways communities resist and find alternatives. We shared stories which have come to us through our research with communities as part of the WEGO network for Feminist Political Ecology.

Through this FPE dialogue, we ask: what does the climate emergency look like in each of these places? How do frontline communities resist ‘false solutions’? Through a toxic tour, we juxtapose untold stories from riverine, forest, agrarian, pastoralist and suburban communities in West and Central Kalimantan (Indonesia), Kenya and the UK. These stories of everyday struggles for life may be overlooked, and therefore untold, in the drama of large-scale resistances. Alongside the tour, we invite those attending in person to join us in an open story-sharing space to gather and connect untold stories from elsewhere.

We also bring these stories to the United Nations COP26 Virtual Gender Marketplace to bring our FPE perspective into conversation with policy makers alongside bodies including IUCN, UN Women and others engaged with gender and the climate agenda.

Full post here.

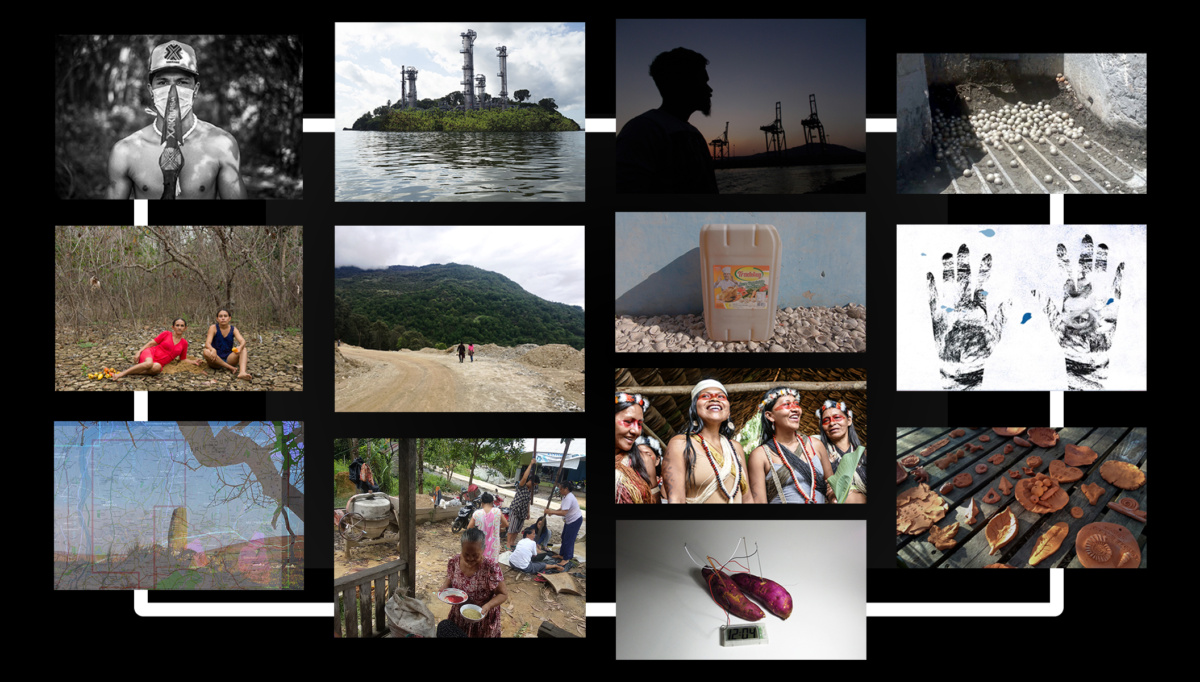

Despite Extractivism Exhibition

Despite Extractivism is an online exhibition that assembled expressions of care, creativity and community in relation to diverse extractive contexts. The exhibition is both an exploration of extractivism, and of the already-existing alternatives. Collectively, the works in this exhibition illuminate and explore ways of questioning, subverting and resisting the violent logics and impacts of extractivism. The FPE dialogues event series provokes questions and discussions with communities, creatives and activists. Whilst our questions are informed by Feminist Political Ecology (FPE), the dialogues provide an opportunity to push FPE in new directions.

In addition to the co-curation of an online exhibition following on from the Extracting Us exhibition series, the organising team organised a series of online webinars which were spaces where artists, activists, researchers and interested audiences could convene to explore extractivism and its alternatives through a FPE lens. Between a launch event and a closing event, three webinars explored the stories, ideas and practises of the Despite Extractivism contributors and the communities they engaged with. The events, featuring performances, presentations and discussions, focused in turn on expanding but intersecting scales, from the body to the global.

Full post here.

Access to the webinars here: